We often see businesses assume they’re in control because they have a spreadsheet with numbers in it. I’ve been guilty of this.

We see people make a plan and then puzzle at that plan when things don’t match up.

Sometimes this results in making a new plan. And 12 plans later you run out of trust that these plans are working. You have “numbers on a screen” syndrome.

A plan that provides a false sense of security can be worse than having no plan at all.

What a forecast or financial control process needs are consistent attention and fine-tuning. If your forecast was off track you need to know why or it stops being useful.

Some people use budgets. Some use forecasts (see here for the difference). Most use both. What we’ve found is that granular forecasts help highlight problems faster. They create realistic expectations rather than “numbers on a screen”.

It’s then important to operationalise these numbers. To make sure cash flowing in and out of the business matches your model or you’re living in two different worlds.

A common scenario when your cash balance doesn’t match your forecast is to dig into the numbers to figure out why.

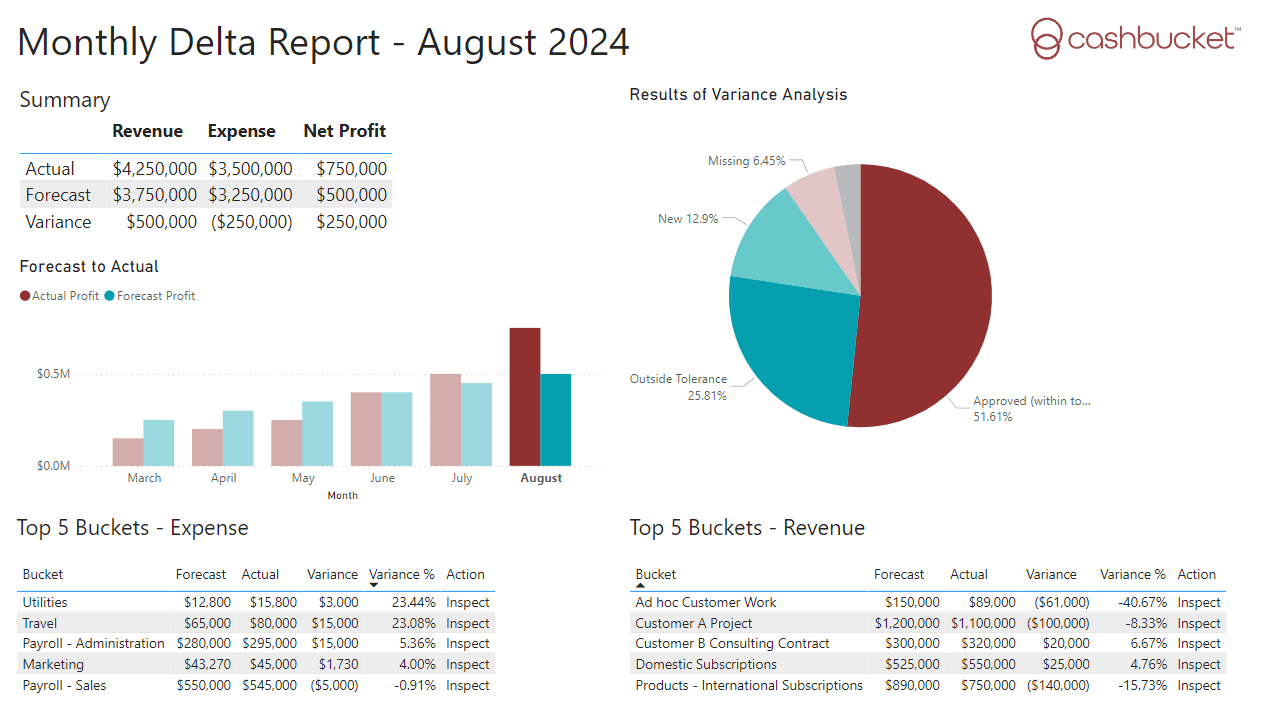

We use buckets and run comparisons between what we thought would happen and what did happen. We then drill in to these buckets and find out which items

- Came in as expected

- Came in but were different to what we expected.

- Are completely new

- Were mistimed

- Didn’t come in at all.

4 of the above rules drive action. They tell you you need to investigate, chase or question. These actions and keeping expected versus actual consistent are what keeps things meaningful. The operational part of cash management that means you don’t just have “numbers on a screen.”